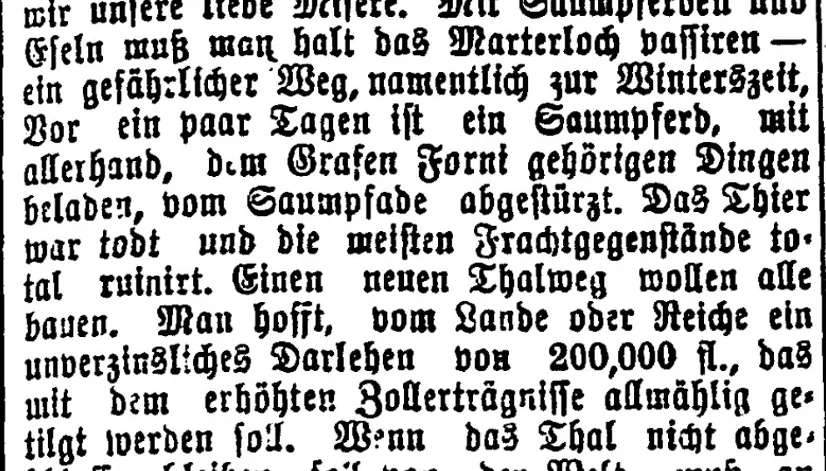

Just above the Marterloch gorge lie the farms of Martertal and Eirnberg (formerly known as "Eyrnberg"). Due to their location along the historic mule track from Bolzano/Bozen to the Sarn Valley, they served for centuries as an important resting place for merchants, carriers, and mule drivers.

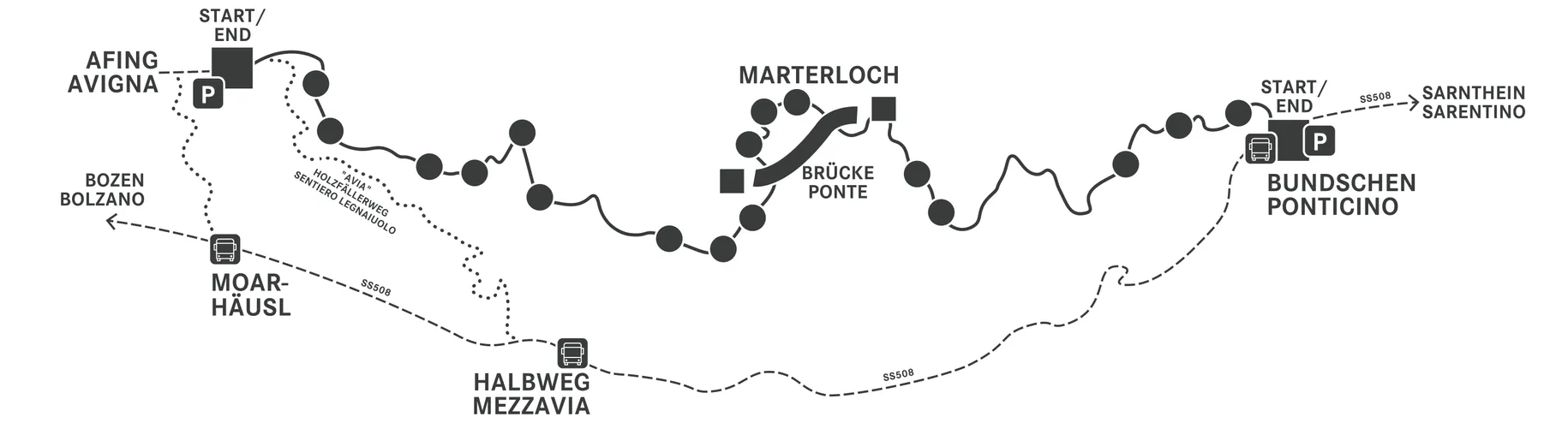

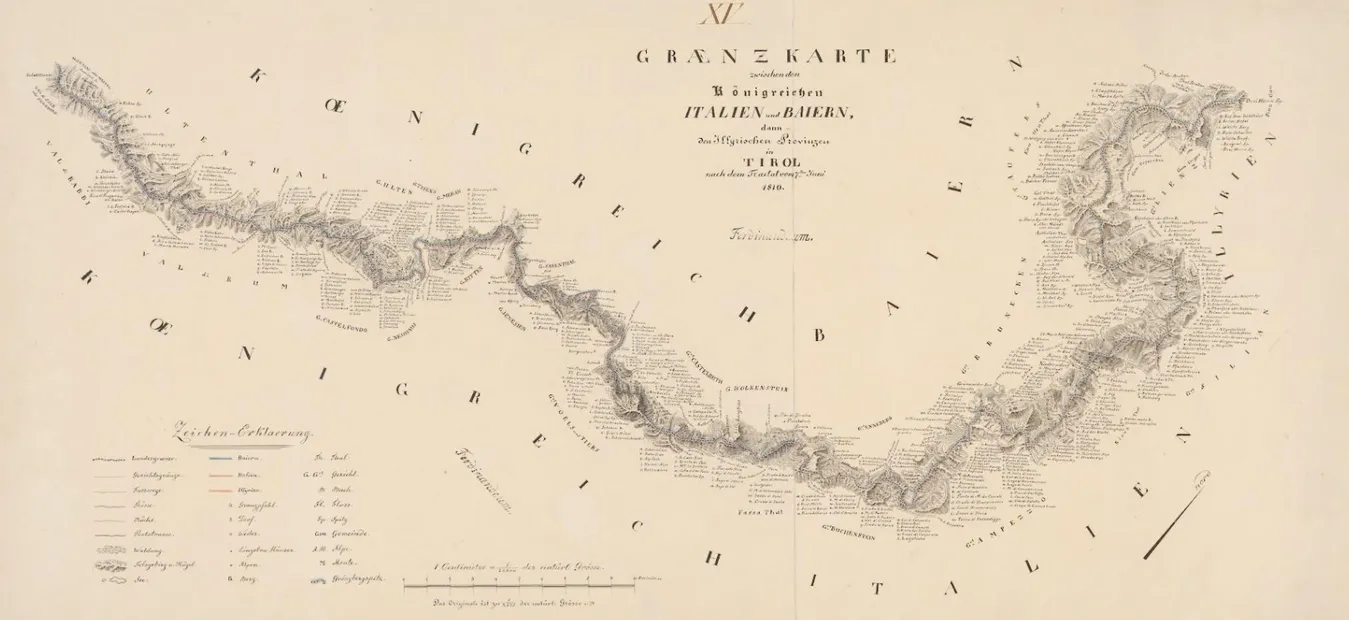

The path led from Bolzano/Bozen via Castle Rafenstein and Afing, through the Marterloch and down to Bundschen and into the valley. A proper road was not built until 1900 – before that, the route along the Talfer River was frequently destroyed by floods and often impassable.

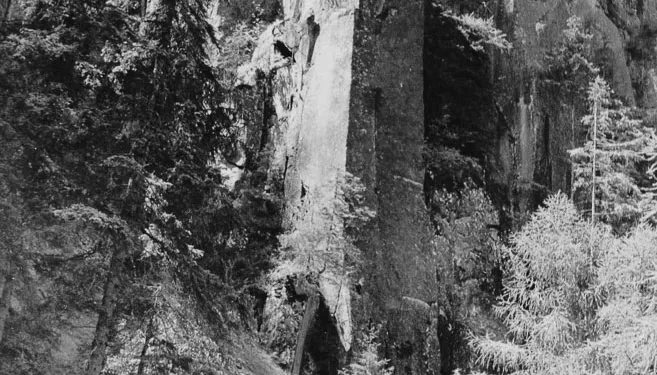

Eirnberg Farm was more than a typical farmstead: featuring a Romanesque archway and a fortified tower with loopholes, the owner was responsible for maintaining the path and was granted the privilege of serving wine. He was also obliged to offer lodging and protection to travelers. The stables could accommodate up to 40 horses.

According to legend, the site was already used during Roman times as a guard post and refuge, allegedly established by the Roman general Drusus.

A Final Greeting at the Martertal Spring

A story inspired by the Sarn Valley

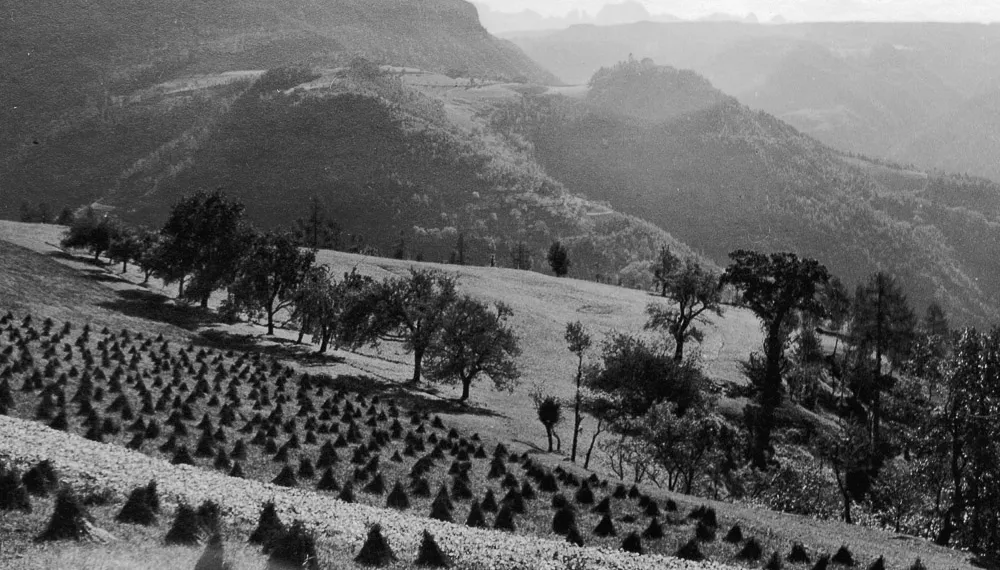

An autumn evening settles cold and quiet over the slopes between Rafenstein Castle and Vormeswald. Along the old mule track, which winds from Bozen through Afing and the Marterloch to Sarnthein, a man walks alone. Time has left its marks on his face. His clothes are worn, the outlines of an old valley costume barely visible. At the spring deep in the gorge, he stops. He sits down, weary, and gazes across at the farm on the opposite side – still and unchanged, like a memory made stone.

It has been ten years since he last drew water here. Ten years since he said goodbye to a young woman named Marta – quiet, blonde, with clear eyes. It was 1810. The valley had to send thirty men to war. The lot fell to his younger brother, but the man at the spring stepped in for him. “Take care of the farm until I return,” he had said. And then he left. With an army bound for Russia. Few returned. He was among them.

Now, in 1820, he is back. Smoke rises from the chimney. The meadows are tended. Nothing seems to have changed. But then a child appears. Blonde, blue-eyed. He says his mother is called Marta, his father Sepp. Four children live at the farm. Sepp – the brother.

The man smiles faintly. He knows there is no place left for him. His sacrifice was silent – and forgotten. In a quiet voice he tells the child: “Tell your mother someone who never forgot her was at the spring today.” Then he turns. Walks the old path down again – through the Marterloch, past Afing, past Rafenstein – and away. For the second and final time.